- how testing is influenced by other activities and strategies in the organisation,

- where our competitors and the wider industry are heading, and

- what the testers believe to be important.

I prefer to seek answers to these questions collaboratively rather than independently and, having recently completed a round of consultation and reflection, I thought it was a good opportunity to share my approach.

Consultation

In late March I facilitated a series of sessions for the testers in my organisation. These were opt-in, small group discussions, each with a collection of testers from different parts of the organisation.

The sessions were promoted in early March with a clear agenda. I wanted people to understand exactly what I would ask so that they could prepare their thoughts prior to the session if they preferred. While primarily an information gathering exercise, I also listed the outcomes for the testers in attending the sessions and explained how their feedback would be used.

***

AGENDA

Introductions

Round table introduction to share your name, your team, whereabouts in the organisation you work

Transformation Talking Points

8 minute time-boxed discussion on each of the following questions:

- What is your biggest challenge as a tester right now?

- What has changed in your test approach over the past 12 months?

- How are the expectations of your team and your stakeholders changing?

- What worries you about how you are being asked to work differently in the future?

- What have you learned in the past 12 months to prepare for the future?

- How do you see our competitors and industry evolving?

If you attend, you have the opportunity to connect with testing colleagues outside your usual sphere, learn a little about the different delivery environments within <organisation>, discover how our testing challenges align or differ, understand what the future might look like in your team, and share your concerns about preparation for that future. The Test Coaches will be taking notes through the sessions to help shape the support that we provide over the next quarter and beyond.

***

The format worked well to keep the discussion flowing. The first three questions targeted current state and recent evolution, to focus testers on present and past. The second three questions targeted future thinking, to focus testers on their contribution to the continuous changes in our workplace and through the wider industry. Every session completed on time, though some groups had more of a challenge with the 8 minute limit than others!

Reflection

From ten hours of sessions with over 50 people, there were a lot of notes. The second phase of this exercise was turning this raw input into a set of themes. I used a series of questions to guide my actions and prompt targeted thinking.What did I hear? I browsed all of the session notes and pulled out general themes. I needed to read through the notes several times to feel comfortable that I had included every piece of feedback in the summary.

What did I hear that I can contribute to? With open questions, you create an opportunity for open answers. I filtered the themes to those relevant to action from the Test Practice, and removed anything that I felt was beyond the boundaries of our responsibilities or that we were unable to influence.

What didn't I hear? The Test Coaches regularly seek feedback from the testers through one-on-one sessions or surveys. I was curious about what had come up in previous rounds of feedback that wasn't heard in this round. This reflected success in our past activities or indicated changes elsewhere in the organisation that should influence our strategy too.

How did the audience skew this? Because the sessions were opt-in, I used my map of the entire Test Practice to consider whose views were missing from the aggregated summary. There were particular teams who were represented by individuals and, in some instances, we may seek a broader set of opinions from that area. I'd also like to seek non-tester opinion, as in parts of the organisation there is shared ownership of quality and testing by non-testers that makes a wider view important.

How did the questions skew this? You only get answers to the questions that you ask. I attempted to consider what I didn't hear by asking only these six questions, but I found that the other Test Coaches, who didn't write the questions themselves, were much better at identifying the gaps.

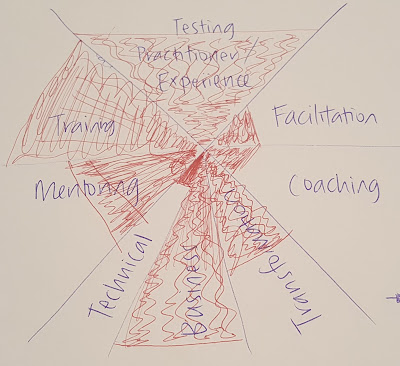

From this reflection I ended up with a set of about ten themes that will influence our strategy. The themes will be present in the short-term outcomes that we seek to achieve, and the long-term vision that we are aiming towards. The volume of feedback against each theme, along with work currently in progress, will influence how our work is prioritised.

I found this whole process energising. It refreshed my perspective and reset my focus as a leader. I'm looking forward to developing clear actions with the Test Coach team and seeing more changes across the Test Practice as a result.